When Agatha Christie's The Murder of Roger Ackroyd was published in 1926, it featured a twist so sensational for its time that it shocked even the most seasoned readers. If ever there was a work that, at face value, so blatantly upended one of the cardinal rules of crime fiction back then, it is this one.

|

| Roger Ackroyd appears: The first UK edition |

Today, the trope of the unreliable narrator is one of the most clichéd in fiction—a device you can spot coming a mile off, whenever there's reasonable doubt to suspect that it's been introduced. However, for authors, it is a far trickier prospect to execute successfully than many may be led to believe initially. In particular, Christie's treatment of the trope in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, is all about subtlety. After all, this is not a case of a central character simply spouting outrageous lies and later getting exposed. The genius of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd lies in the culprit's expertise in managing and controlling the flow and revelation of information as he deems fit—he may be reticent and picky about what strands of information he chooses to expose judiciously and cunningly, but never does he lie outright.

How, then, does one adapt a work whose virtues have become all too familiar to the audience and still keep it fresh? It's not an easy task, as is evidenced by the failure of David Suchet's Poirot (2000) in doing justice to The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. In its quest to present something new to the viewers and mark itself as something very different from Christie's work, this particular TV episode does away with all the key features that made the novel such a landmark one in the first place. Character roles are changed drastically, events are inexcusably altered, and to cap it all off, the conclusion fails to pack the desired punch.

However, Japanese author, screenwriter and director Kōki Mitani's adaptation of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, titled Kuroido Goroshi (2018), succeeds where Suchet's fails. Among literary circles, Mitani is popular and much beloved for his mystery and comedy works, one of which is the excellent TV series, Furuhata Ninzaburō (1994–2006)—in many ways, the Japanese version of Richard Levinson and William Link's legendary inverted mystery series, Columbo. All of his trademarks are also present, in varying degrees, in Kuroido Goroshi—a TV special that offers some clues on how to adapt a tricky work such as The Murder of Roger Ackroyd correctly and proficiently.

As is the case with Furuhata Ninzaburō, one can sense Mitani's love and respect for the source material in Kuroido Goroshi. Instead of 1920s countryside England, one is transported to the picturesque village of Tonosato in 1952 Japan—a setting that most reminds me of fictional Midsomer (in Midsomer Murders) with its gossipy villagers and sleepy manors and cottages sheltering dark secrets. The adaptation is very faithful to the novel and the events that transpire henceforth should therefore be familiar to most readers who are acquainted with Christie's book. Additionally, Mitani gives a few distinctive touches—strengthening the portrayal of characters, making the motives behind their actions meatier and making it more difficult to guess whodunnit, making subtle changes to the timeline of events, more foreshadowing, introducing characters that would make sense in a Japanese setting, among others—that significantly contribute to the lasting legacy of the work.

The film opens with an interaction between Takeru Suguro (the Hercule Poirot equivalent) and Dr Heisuke Shiba (Dr Sheppard's character) in Tonosato village (similar to King's Abbot). Heisuke happens to be the only practicing doctor in the village who, on the side, has been writing a manuscript investigating the circumstances of the death of Rokusuke Kuroido, one of the notable personages in the village and a close acquaintance of Heisuke. It is through the pages of Heisuke's manuscript (that is handed over to Takeru in the opening few minutes of the film) that we see the film's narrative unfold as well. This narrative-within-a-narrative treatment, along with the help of a clever shifting timeline, allows Mitani to portray one of the most difficult aspects fairly well (but not flawlessly—things get a wee bit muddled towards the end).

Rokusuke's murder happened in mysterious circumstances after a family dinner to which Dr Shiba had also been invited. Later, Takeru is called in to solve the mystery by Rokusuke's niece Hanako, while Heisuke, who was completely unaware of Takeru's reputation as a meitantei (great detective) at this time, becomes his Watson. The TV special reconstructs the events of the novel without skipping on too many details—Heisuke being invited to Rokusuke's study for a secret conversation with the secret remaining unsaid, a lot of curious incidents involving the other occupants of the house around the estimated time of murder, a rather small but strange change in the arrangement of a particular piece of furniture at the site of crime (Rokusuke's study) which is then reverted to normal, a mysterious phone call to the doctor's house that leads to the corpse's discovery in the first place and the suspicion ultimately falling on Rokusuke's stepson Haruo are exact replicas of what happens in the book.

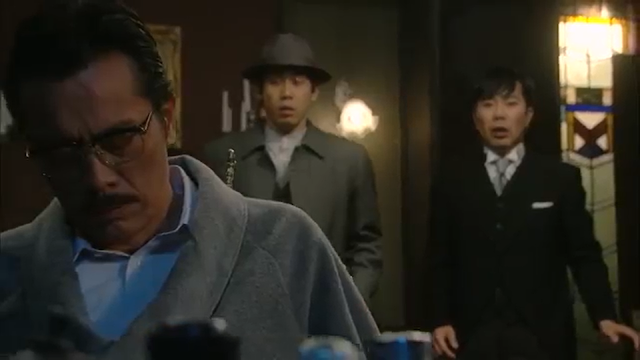

|

| Roger Ackroyd dies again, this time as Rokusuke Kuroido |

All of this sounds rather heavy and foreboding. Moreover, there are too many innocuous, inconsequential distractions all cluttered roughly around the same time as the murder that threaten to take one's attention away from the central plot. But, in Mitani's hands, these turn out to be the perfect spots to bring in comic relief. No doubt, the comedy and parodic elements are sometimes laid on a bit too thick for my taste, but segments such as the absconding Haruo's reappearance in the village before the shocked sister of Haruo, the childish tantrums of Rokusuke's spoilt sister, the village police inspector indulging in a bit of fanboyish admiration of the famous ex-detective Takeru and Rokusuke's overeager secretary completing every sentence and observation of the inspector (before the latter has the chance to do so) much to his annoyance genuinely strive to put a smile on one's face. The revelations are also done in a lighthearted manner, resulting in a special that competently balances a serious investigation with comic storytelling, barring some excesses.

Still, Mitani shines brightest when he puts sombre touches on his portrayal of events and characters. This becomes all too evident during the conclusion when, despite all his eccentric mannerisms, Takeru is finally dispel all the chicanery and the facades to reveal the true nature of the case. We are then left with the culprit all to himself contemplating suicide, his thoughts serving as an epilogue to the episode and the manuscript with which it opens. The extra-layered motive behind the culprit's necessary actions lends Mitani's adaptation a human quality easy to empathise with, which is completely absent in Christie's original. The final fates of the doctor and, especially, his ebullient, gossipy sister leave one in a reflective, poignant, even mournful, mood in sharp contrast to all the humour and adrenaline-pumping fun experienced during Takeru's deductions.

The way the story unfolds also lends itself to a comparison with another manor mystery (an adaptation of another book, by the way) I had watched and reviewed some months ago—Akuma ga Kitarite Fue wo Fuku. This Kosuke Kindaichi mystery unravels in real time (barring a few flashbacks), with the telltale clues, conversations observations and the reasoning leading to the deductions all laid bare before the reader, before the grand deduction leads the detective to reveal the even deeper mystery of 'what really happened' which even the culprit wasn't aware of. There's little by way of distractions and the focus on the core mystery is really intense leaving little else to the imagination. Kuroido Goroshi, on the other hand, transitions from the past to the present within the pages of a manuscript presenting a mix of limited first-person and third-person perspectives. Side plots abound in plenty, most of which are tied to the main storyline with the flimsiest of threads, but which, at times, threaten to steal all the limelight for themselves. The main trick is a neat one, involving a nice bit of deception involving [SPOILERS AHEAD] a dictaphone, a telephone call, and a strategically placed chair and pile of books, the combined effect of all these evidences successfully leading the investigators to wrongfully estimate the time of death.

But, the real charm of Kuroido Goroshi lies in its depiction of the battle of wits between the culprit and the meitantei. Unlike Akuma ga Kitarite Fue wo Fuku, Kuroido Goroshi does not exactly show the ace detective's thinking (or rather, his little grey cells in action). Even though the clues leading to said thoughts are all presented in order, there's a jump between their presentation and the accurate inference during the deduction scene. Like many of the audience members, one is surprised and left to wonder how Takeru chanced upon the exact interpretation of said clues to deliver a remarkably correct inference. Seen in isolation, it can be quite frustrating and seen as not quite fair to the reader. But, when one keeps in mind the overarching theme of the novel and this adaptation, this treatment makes sense and is, in fact, deliberate. As mentioned previously, the main theme of both the novel and this adaptation is that of deceiving readers and viewers through cleverly concealing information, revealing the bare minimum, and never by outright lying. And since the excessively modest culprit chooses to be courteously evasive throughout and reveals only bits and pieces about his participation in the events and his thoughts on the investigation, so does Takeru. Takeru needs to beat the culprit at his own game—and so, he never reveals his ways of thinking and reasoning to even his closest associates or the viewers. Not surprisingly, this explains the jump between observation and deduction (which mostly happens off-screen) as not even the author of the manuscript is privy to these details in the first place. It is a very effective ploy befitting of the master detective, which goes on to surprise and draw the real culprit out of his shell who finally 'confesses' to his wrongdoing and his underestimation of Takeru in the end.

|

| Takeru Suguro: Japan's Hercule Poirot |

Kuroido Goroshi is not the only TV special where Mitani has showcased his brilliance in adapting the Dame's works. Prior to this, he adapted Murder on the Orient Express (in 2015) as a two-episode TV drama special featuring Takeru Suguro. While the first episode shows the events of the novel unchanged, the second is a splendid imagination and portrayal of how the perpetrators were going about their lives and daily duties in the lead-up to the murder on the train—a completely new perspective and behind-the-scenes look entirely absent in the novel. And after Kuroido Goroshi, he has also adapted Appointment with Death (Shi to no Yakusoku, 2021) which I am yet to see. Seen as a tribute to one of Christie's iconic works or as a standalone TV special in its own right, Kuroido Goroshi is deserving of several rewatches. One hopes that the same is true of the rest of Mitani's Christie-based output. Whatever may be the case, based on my fervid enjoyment of Kuroido Goroshi and my currently skyrocketing expectations, I plan to write more on Mitani's works, as and when I come across them.