Observing the similarities between four unlikely, disparate works of crime fiction—Edogawa Rampo's

Nisen doka (Two-Sen Copper Coin, 1923) and Agatha Christie's

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926) on one hand and Rampo's

Inju (The Devil in the Shadow, 1928) and Dashiell Hammett's

The Maltese Falcon (1930) on the other—Sari Kawana states that these commonalities "question the myth of direct influence in that occasionally what appears to be the result of direct influence is in fact the consequence of the permutation of similar generic rules." She goes on to say, " ... the sequence of events suggests that Rampo and Christie detected the same generic convention and decided to permute it in the same way, making a conscious choice to exploit the naivete of such an assumption and using it to entertain readers" and that " ... the case of Rampo and Christie calls for a new way of looking at various formalist literatures and cross-cultural literary inspiration and encourages the willingness to go beyond the existent hierarchy of influence and de-emphasize originality and priority."

Concerning Rampo and Hammett, Kawana states the following: " ... the striking similarity between Hammett's and Rampo's works should be viewed as evidence potentially pointing to at least two theories. From the standpoint of social history, it can serve as another piece of evidence potentially what critics Yoshimi Shun'ya and Harry D. Harootunian have called sekai dojisei (global simultaneity), the emergence of a global culture to which the United States, Europe, and Japan belonged.

Another more formalist explanation would be that Hammett and Rampo, both students of the formulas and techniques of detective fiction, arrived at the same conclusion via different paths. ... "

The truth, when it comes to the evolution of Japanese crime fiction, perhaps lies somewhere in between. While the theory of global simultaneity holds firm, especially during the Inter-War period, there's also no denying that Japanese crime-fiction authors did, unabashedly, look to the West for influence and even inspiration after World War II. Seishi Yokomizo, long considered a doyen of crime fiction in the Japanese literary world, perfectly illustrates this in The Honjin Murders, where the unnamed narrator tries to think of any western counterparts to the case he is about to introduce to the readers—John Dickson Carr's The Plague Court Murders, Gaston Leroux's The Mystery of the Yellow Chamber, S. S. Van Dine's Canary Murder Case and Kennel Murder Case, Royal Scarlett's Murder among the Angells, among others. But, he then concludes that this case is not at all similar to these illustrious works—an admission that suggests that The Honjin Murders is not a plagiarised work. Yokomizo then presents a work that is uniquely Japanese in essence, but which curiously enough "neither declares nor refutes its uniqueness"—an observation made evident by the narrator's comment that the culprit may have read the aforementioned books and used their elements to their advantage.

The fact that Yokomizo openly admits to his inspirations (the narrator, in the end, says that they learnt to deceive the readers by taking hints from Agatha Christie's works) hints at a new way of dealing with the originality/unoriginality debate that rages on even today in the world of crime fiction. In the book, Yokomizo merely uses some tricks (they would have been common and popular knowledge among crime-fiction aficionados at that time) to explore new avenues and to further develop his own plot. It is a stratagem fraught with risks (especially when it comes to the degree to which you can 'borrow' and 'be inspired' in such a way), but for a self-respecting, clever writer, such an approach can be useful.

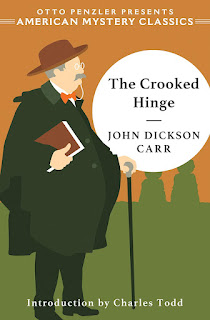

For the observant reader, on the other hand, pinpointing these unconventional points of intersection between works separated by space and time can be instructive. Moreover, with the benefit of hindsight and a retrospective lens, one is likely to come across more instances of twinning in detective fiction, many of which can be completely accidental. For instance, one wouldn't usually speak of Carr's The Crooked Hinge (1938) and Yokomizo's Akuma ga Kitarite Fue wo Fuku (The Devil Comes Playing His Flute, 1951–1953) in the same breath. And yet, the 'similarities' between the two definitely deserve a closer look.

Automatons, Satanism, The Tichborne Claimant, The Titanic, Witchcraft

At the core of the devilish proceedings in Carr's

The Crooked Hinge lies an impersonation inspired by the

infamous Tichborne case in the 1870s, where an Australian butcher by the name of Arthur Orton unsuccessfully tried to lay claim to the Tichborne baronetcy impersonating the deceased Roger Tichborne, after the other heir (Alfred Tichborne) had passed away. In Carr's work, the peace and quiet of a Kentish village is broken with the arrival of a certain Patrick Gore, who claims to be the true inheritor of Farnleigh Close, an ancient mansion currently occupied by Sir John Farleigh (a title Gore also lays claim to), his wife Molly, their butler Knowles and a small housekeeping stuff.

As was the case with Arthur Orton and Roger Tichborne, the intriguing bit is that Gore and Farnleigh do not resemble each other at all in their facial looks. However, during the inquest to determine the legimitacy of the real Sir Farnleigh, it transpires that both 'claimants' are privy to facts that only the real deal would know. And really wild facts they are: turns out there was a 'role-reversal' on the sinking Titanic that was carried out so successfully that no party on either side of the Atlantic was able to notice the deception—'Patrick Gore' landed in a circus troupe in America after being rescued from the Titanic while 'Sir John Farnleigh' inherited the mansion and married his childhood sweetheart. It is in the midst of a break in these proceedings that the current occupant of the mansion, Sir John Farnleigh, has his throat slashed and is found floating in a pool surrounded on all sides by a five-feet border of sand and thick hedges that block its view. It is witnessed by three separate people all of whom claim to have seen no one in Farnleigh's vicinity. At the same time, a thumbograph recording the fingerprints of both Farnleigh and Gore is stolen from the library.

At this point, in comes Dr Fell after being apprised of the developments. Things start moving at a feverish pace henceforth, and Carr lays it very thick, especially with the atmosphere which is menacing, infernal and has a touch of

Death Watch (an earlier Dr Fell novel) to it. An automaton suddenly brought to life, the Golden Hag (modelled after

Maelzel's Chess Player), scares the living hell out of a housekeeper and then tumbles down the stairs from the topmost floor almost killing Dr Fell. Rumours of satanism and witchcraft start making the rounds, and the damaged automaton later reappears at the doorstep of a neighbour, also managing to 'orchestrate' the unsuccessful shooting of a bullet at one of the characters. Dr Fell, however, plays his own game, managing to unravel the truth and also present a false, exaggerated solution to lure the weak link (surprise, surprise, it's the butler!) into making a confession of what really happened and his role in it all.

Probably, only an imagination as fertile as Carr's could have come up with a plot that manages to tie together elements as far removed from each other as automatons, the Titanic, the Tichborne Claimant, witchcraft and Satanism. Regretfully, though, this is one of those efforts where the individual components outshine the sum and combined effect of all of the parts. There are many incredibly attractive plot threads that end on disappointing notes. The fake Patrick Gore's (and in turn, Carr's) explanation of the operation of the automaton, for instance, has often been considered to be dodgy and suspect, especially as it seems to echo

Edgar Allan Poe's mistaken ideas on how the Maelzel Chess Player actually functioned. More importantly, the conclusion makes the very addition of the automaton feel cheap, almost like a cop-out—especially as it only exists to scare a character from accidentally making a discovery the significance of which they may not even realise, while the automaton's second appearance feels worse than an afterthought, and is incredibly childish and damning for the perpetrators given their 'satanic' credentials. The digressions on witchcraft, illusionist practices, Satanism sometimes feel too contrived and overwhelm the central narrative too much in the name of atmosphere—all of which are effectively rendered null and void by the killer's epistolary admission to Dr Fell.

I am equally torn about the solution to the murder of Sir John Farnleigh. I absolutely love the completely-bonkers, didn't-see-it-coming aspect to it, especially as it plays upon our perceptions of height and how one can 'disguise' themselves taking advantage of these perceptions. At the same time, it comes across as a convenient deus ex machina without sufficient clueing prior to its revelation—and even with the clues observed by Dr Fell, it will be quite the stretch for you to identify the exact contraption used (or not) to make the illusion possible. And even though I find the reason to how three witnesses were cheated satisfactory (if not a bit too dependent on luck), there's one major problem with the solution. It fails to help me envision how the culprit escaped from the pond without leaving any print whatsoever on the five-feet border of sand surrounding it on all sides. That must have been a miraculous achievement, given what the killer suffered from. And as they say, in crime fiction, even miracles need to have a rational basis. Sadly, I could find none in this case in which these prints could have been a dead giveaway and a major setback for the culprit early on.

Japanese Nobility, Seances, The Devil, The Teigin Incident, Three-Fingered Clues

Much like

The Crooked Hinge, Yokomizo's

Akuma ga Kitarite Fue wo Fuku has a real-life incident in its backdrop—

the 1948 Teigin case, in which a person masquerading as a public health official poisoned 16 employees of the Imperial Bank in Toshima, Tokyo by telling them that he was inoculating them against an outbreak of dysentery. Twelve people died as a result, while the killer made off with 16,000 yen.

As with The Crooked Hinge, impersonation plays a critical role in this work as well—here, in the form of a strong facial resemblance between two important characters. Apparently, Yokomizo was inspired to write the novel when a fellow writer confessed that his face closely resembled that of the alleged culprit, going by the killer's composite picture released by the police. For his part, Yokomizo kept most of this setting intact, only replacing the bank with a jewellery store called Tengindo.

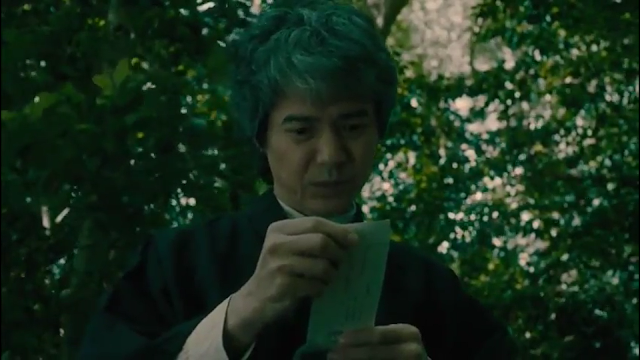

To read the novel though, one needs to have a thorough grasp of Japanese as it hasn't been translated yet. The best you can probably do, if you are unable to read the book, is to watch a 2018 adaptation (a TV special) by NHK, a Japanese broadcasting agency (

this shoddy print exists on YouTube). Side note: this is only one of the several adaptations over the decades; I personally prefer the late 1970s episodes (with Ikko Furuya in the lead), a subbed version of which once used to come up on YouTube, but alas, that's gone.

|

| Hidetaka Yoshioka as Kindaichi |

Anyway... Master sleuth Kosuke Kindaichi receives a most unusual request from one Mineko Tsubaki: to investigate the death of her father, Viscount Tsubaki, and to find out if he is actually deceased or not. As it turns out, a few months ago, acting on an anonymous tip-off, the police took the Viscount into their custody on suspicion of having committed murders and an enormous robbery at the Tengindo jewellery store in Tokyo. He is eventually released; strangely enough, he soon commits suicide, but not before cryptically warning his daughter (both verbally and in a note) that 'the shame is too much for him to bear', that 'in the Tsubaki mansion, the devil resides', and that 'the devil comes, playing his flute'. He spends his last few days playing the eerie tunes of his last composition on his flute. The spark for Mineko's visit to Kindaichi, however, is the fact that a few days ago, the mistress of the mansion (Mineko's mother, Akiko) and a servant (Mishima Totaro) both claimed to have seen the deceased viscount in a packed theatre. Kindaichi thus finds himself invited to a seance (to be conducted at the behest of Akiko) at the Tsubaki mansion, where the participants will try to communicate with the deceased patriarch.

If this foreboding atmosphere reeks of the devil (in essence, almost reminiscent of the inquest scene at Farnleigh Close in The Crooked Hinge), it's a fitting one. For, the seance, aided by two blackouts, literally summons the symbol of the devil on the table where it is being conducted! At the same time, the sinister tones of Viscount Tsubaki's float into the seance room, sending everyone into a frenzy. And all this is only the beginning of an extremely complicated case, as, the very next morning, Mineko's uncle (Count Tamamushi) is found murdered inside the locked seance room.

|

| At the scene of the seance |

Both in

The Crooked Hinge and in

Akuma ga Kitarite Fue wo Fuku, readers and viewers are assailed by the sense that most of the characters are floundering in fathomless darkness, in the sense that they are unable to truly get a grip on whatever's happening around them. But, in the latter's case, the real 'heart of darkness' concealed by layers and years of deception and depravity is sufficient to drive any sane person truly insane. This dark, depressing potential is supposedly never fully realised in the novel (which ends on a hopeful note), but the 2018 adaptation is more than happy to emphasise these elements in the extreme, especially with the wholesale changes it makes in the long concluding stretch, and will you leave you feeling absolutely hollow at the end of it all (for a comprehensive list of the differences between the novel and this adaptation,

head over here).

Things happen in this TV special, and a lot of them too—more murders, including one far from Tokyo that has a direct bearing on the case, a lot of past history for which Kindaichi has to travel elsewhere, a disappearing flute case, a part of the Tengindo loot suddenly reappearing, words disappearing from a stone lantern (the equivalent to the automaton incident in The Crooked Hinge, in my opinion), among others. But this is not an action movie by any stretch of the imagination—on the contrary, most of it consists of Kindaichi striking up conversations with people that later provide valuable insights into the case.

Still, the clues are littered throughout the episode in a way that never leaves you bored. For example, linguistic differences—the subtle difference in the way common words are pronounced in different regional dialects (facts Kindaichi gleans while conversing with people)—help the ace detective figure out whodunnit. It is also a great example of how a single word and its correct interpretation can completely turn a mystery on its head. Above all, rarely will one come across such a glaring, in-your-face dying message that remains so cunningly hidden till the end—Viscount Tsubaki's last musical score that Kindaichi comes to understand, at the very end, would have helped him realise who the perpetrator was at the very beginning and thereby prevent all the murders. Tragic indeed.

Unlike The Crooked Hinge, none of these diverse elements are irrelevant to the central mysteries. There's a synergy between all the events (something that is lacking somewhat in The Crooked Hinge) that makes for a linear, intense storyline. And this adaptation focuses most on the motive aspect, with a nearly hour-long conclusion. The locked room is explained in a matter of minutes (not counting the false solution proposed in the opening stretch), demonstrated in a comic, matter-of-fact way, and so is the explanation of how the devil's symbol appeared on the seance table (a clever switching identical-looking, 'twin' statues at an opportune moment). Kindaichi himself points out that he would not be able to come to the truth as long as he thought about 'how' or 'why', he needed to know 'what': what really happened in Count Tamamushi's villa in Kobe during the summer of that year long ago?

|

| Kindaichi visits the stone lantern at the site of Count Tamamushi's ruined summer palace in Kobe. The devil was born here |

The incident (or incidents) at the heart of the affair is truly horrific (nauseating would be an understatement) and, aided by complicated happenings later on, adequately explains why the relations between nearly all of the characters are so insanely complicated, frankly unbelievable (in this aspect, it resembles Victorian-era novels with long, intricate family trees). There are two aspects to this that I particularly like. One is that the motive directly ties in with the themes Yokomizo explores in his work: namely, the sheer depravity of the Japanese nobility, the bottomless depths of this depravity, the nobility's fraught relations with the lower classes and the detrimental effects of this relation, as well as the ways in which World War II acted as the great leveller that

erased Japanese aristocracy and brought them to the level of commoners.

The second aspect I admire is that not even the culprit is aware of the exact 'what' that motivates and guides his revenge against the Tsubaki family and its full implications. It is the misguided nature of his life and his actions that adds a tragic edge to the already overwhelming darkness (as if that alone wasn't enough). One will find it within themselves to sympathise with this devilish criminal drowning in the blood of people for the longest time without respite. This outburst of sympathy is also due, in large part, to the superb portrayal of Kindaichi who comes across as this pathos-inducing, gentle detective who hesitates and tries his best to conceal the devastating truth to those who would be affected by it the most, only to reveal it which then precipitates the last tragedy, denying the detective any form of solace.

As Kindaichi remarks several times during his deduction, "In a person's quest to know everything, he tends to lose sight of the truth." It is a fitting epithet, indeed, for this adaptation.

***

This has turned into quite the long rant on what I essentially started on a whim and some surface-level thinking on two works I encountered a few months ago. It also probably explains why it reads quite disjointed and on rereading it, I am no longer sure that I have adequately achieved what I set out to. However, this is an exercise I am willing to continue. So, expect more of such comparative studies of 'detective twins'—hopefully, with better and well-thought out selections.